Every winter, when the winds pick up across the mountains of Kabul, thousands of Afghans take to the rooftops with spools of string and handmade kites. This isn’t just a pastime-it’s a national event called Gudiparan Bazii, the Afghan National Kite Championship. It’s not about floating peacefully in the sky. It’s about cutting, dodging, and outsmarting your opponent. The goal? To make your kite the last one flying. And when it happens, the crowd roars.

What Gudiparan Bazii Really Means

The name comes from two Dari words: gudipar means kite, and bazii means game or contest. So, literally, it’s "kite game." But calling it a game undersells it. This isn’t a child’s hobby. It’s a cultural ritual with centuries of history. Afghan kites are not the colorful, soft-paper ones you see at beach festivals. They’re made from thin bamboo frames wrapped in handmade paper, with glass-coated string called gut that’s dipped in crushed glass, glue, and sometimes powdered metal. The string doesn’t just cut-it shreds. When two kites lock in midair, the battle turns into a silent duel of tension, timing, and nerve.The rules are simple: no motors, no wires, no cheating. The winner is the last kite still airborne. The moment a kite’s string snaps, the crowd erupts. People sprint across rooftops, chasing the falling kite like it’s a prize. It’s not just about winning-it’s about claiming the trophy. The last kite in the sky becomes a symbol of honor.

The History Behind the Fight

Kite flying in Afghanistan dates back to at least the 18th century, with roots possibly tracing to Mughal India. But it was during the 1970s and 1980s that Gudiparan Bazii became a national obsession. Even under Soviet occupation and later Taliban rule, people flew kites in secret. The Taliban banned it in 1996, calling it un-Islamic. But Afghans didn’t stop. They flew kites at dawn, on rooftops, with children watching from alleyways. When the ban lifted in 2001, the skies of Kabul filled again. That’s when the first official national championship was held.Today, the event is organized by the Afghan Kite Federation, a grassroots group of former kite fighters turned coaches. They train kids in rural provinces, teach them how to make their own kites, and hold regional qualifiers. The finals take place in late January or early February, depending on the wind patterns. In 2025, over 12,000 participants from 34 provinces competed. The winner, a 14-year-old girl from Herat, flew her kite for 8 hours and 47 minutes before cutting the final opponent. She became a national hero.

The Kite-Making Craft

Making a Gudiparan Bazii kite is an art passed down through generations. It starts with bamboo strips soaked in water to make them flexible. Then they’re bent into a diamond shape, dried in the sun, and glued with rice paste. The paper-often recycled from old newspapers or religious texts-is cut carefully to avoid wrinkles. The string is the real challenge. Each fighter prepares their own gut. They mix glass powder with a paste of flour, water, and sometimes salt. Then they dip the cotton thread, let it dry, and repeat the process up to seven times. A single spool can take days to make. The best strings are so sharp they can slice through a plastic bottle.There’s no factory-made kite in Afghanistan. Every kite is handmade, often by a father teaching his son. Some families have signature designs-a red tail, a blue diamond, a symbol of a village. These aren’t just decorations. They’re identity. When a kite falls, people don’t just chase it. They look for the pattern. If it’s a familiar design, they shout the maker’s name. It’s personal.

The Rules and the Ritual

The championship has no referees. Trust and respect are the only rules. Fighters stand on rooftops, sometimes six stories up, holding their spools tightly. A signal whistle starts the match. No one is allowed to touch another person’s kite. If a kite crashes into a building, it’s out. If the string breaks, it’s out. If the kite gets tangled with a tree or power line, it’s out. But if it’s cut cleanly by another kite’s string, that’s the glory.Before the match, fighters often pray. Some leave a small offering-a coin, a piece of candy-on the rooftop. Others whisper to their ancestors. After the match, winners don’t take trophies. They receive a handmade scarf, a date cake, or a small silver charm engraved with a kite. The real prize is recognition. A child who wins in Herat becomes known across the country. Schools invite them to speak. Radio stations interview them. They become role models.

Why It Still Matters Today

In a country that’s faced decades of war, poverty, and displacement, Gudiparan Bazii is one of the few traditions that unites everyone. It doesn’t care if you’re Pashtun, Tajik, Hazara, or Uzbek. It doesn’t care if you’re rich or poor. All that matters is your kite, your string, and your skill. Girls fly too. In 2024, 42% of participants were female. In Kabul, there are now girls’ kite clubs. They meet after school, practice in abandoned lots, and compete in local tournaments.For refugees in Pakistan or Iran, flying kites is how they stay connected. Families send handmade kites back to relatives in Afghanistan. Some even send videos of their children flying kites in exile. It’s a quiet act of resistance. A way to say: we’re still here.

What You’ll See at the Finals

If you stood on a Kabul rooftop during the championship finals, you’d hear the wind. You’d see hundreds of kites, like colorful birds, dancing in the sky. You’d hear the sharp crack of string cutting. You’d see men and women, old and young, yelling, laughing, crying. You’d see kids climbing onto balconies to catch falling kites. You’d smell the dust, the smoke from nearby tea stalls, the faint scent of glue and paper.There are no sponsors. No ads. No corporate logos. Just people, kites, and the sky. The event is funded by community donations-tea sellers, tailors, teachers. They donate money, food, or time. Volunteers keep the streets clear. Doctors set up first-aid tents. Local musicians play traditional instruments between matches.

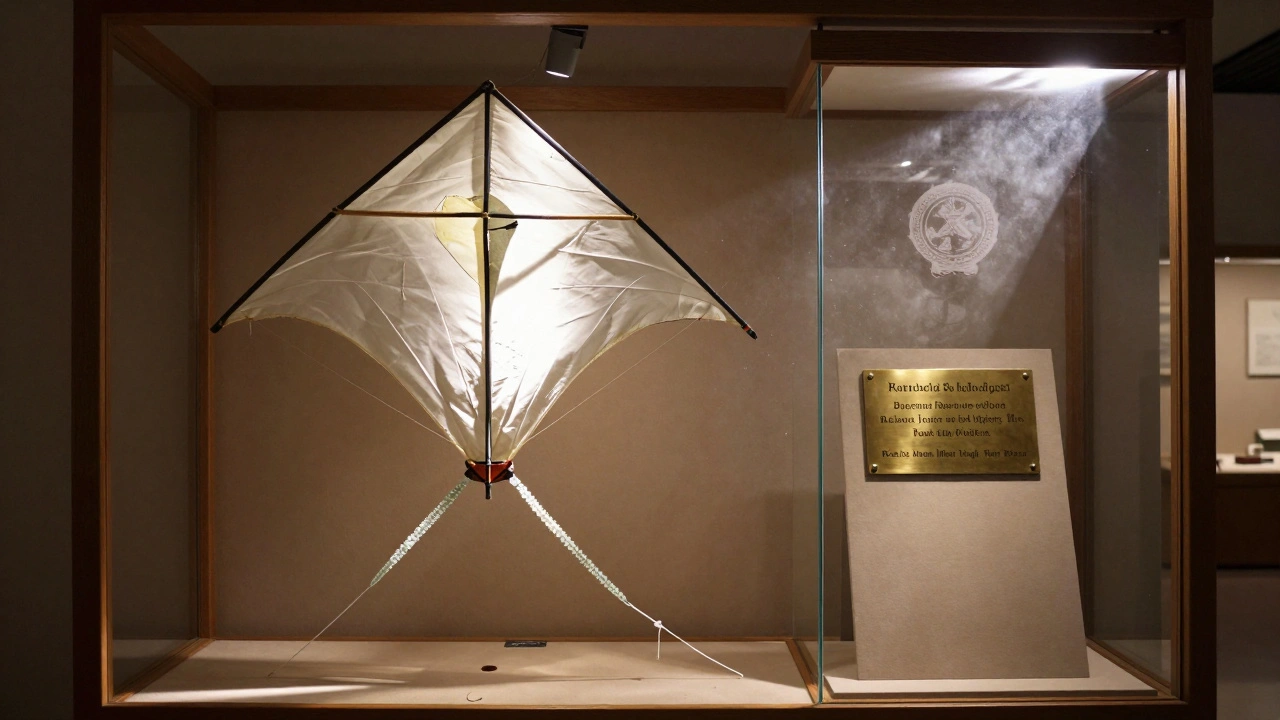

The last kite doesn’t just win. It becomes part of history. The winning kite is displayed for a month in the National Museum of Afghanistan. Its string is preserved. Its name is written in the museum’s ledger. Next year, the child who flew it returns. And if they’re lucky, they’ll fly again.

Is Gudiparan Bazii only held in Kabul?

No. While the national finals are held in Kabul, regional qualifiers take place in cities like Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif, Kandahar, and Jalalabad. Each province holds its own tournament in December and January. The top five winners from each region earn a spot in the national championship. Rural communities often have smaller kite fights in open fields, sometimes with just a dozen participants. These local events are just as meaningful.

Are kites still banned in Afghanistan?

No. The ban was lifted in 2001 after the fall of the Taliban. Since then, Gudiparan Bazii has grown into a nationally recognized cultural event. Even during periods of political instability, kite flying continued in private homes and neighborhoods. Today, it’s officially supported by the Afghan Ministry of Culture and Information.

How dangerous is kite fighting in Afghanistan?

It can be. The glass-coated string can cause deep cuts, especially to fingers and arms. In 2023, over 200 minor injuries were reported during the championship, mostly from handling the string. No serious injuries or deaths have occurred in recent years, thanks to safety measures like gloves, protective tape on spools, and first-aid stations. Children under 12 are required to wear padded gloves during competition. Most injuries happen during practice, not the official event.

Can tourists watch the Afghan Kite Championship?

Yes, but access is limited. The event is open to foreign visitors, but due to security and cultural norms, attendance is restricted to designated viewing areas. Tourists are encouraged to join through official cultural tours arranged by the Afghan Tourism Board. Many visitors come from neighboring countries like Iran, Pakistan, and India. Foreigners are not allowed to fly kites during the championship unless invited by a local team.

What happens to the winning kite?

The winning kite is preserved and displayed for one month in the National Museum of Afghanistan. Its string is carefully removed and stored in a glass case labeled with the winner’s name, age, province, and flight time. The kite itself is mounted on a wooden frame with a plaque. After the display, it’s returned to the winner. Many families keep it as a heirloom. Some donate it to schools or community centers to inspire younger kite fighters.